Everyone Wanted to Pay the Check

- By Mel Corren

- August 17, 2022

- 9:37 pm

- No Comments

Ninth in the Series

As I’ve previously mentioned, none of the GIs who visited me while I was a GI in the Paris Headquarters believed that the cafes on the Champs-Élysées served as our mess halls. When I took them there for meals, they assumed I was treating them.

Even more unbelievable is that when Bob Rieders and I chose not to eat at one of these “mess halls,” we ate in the chef’s invitation-only dining room in the basement of the Majestic Hotel, which was the headquarters of our Commanding General John Lee and later the site of the signing of the treaty that ended the Vietnam War.

Bob and I had an open-ended invitation to eat there at the long table where the French chef held court. Our invitation was a perk that our commanding officer arranged with one of his counterparts. I suppose you might call it a quid pro quo.

It was there that I had a very close encounter with the general. We had just finished eating breakfast at the Majestic, and Bob and I were about to go our separate ways when we ran smack into our general and his entourage.

I was dressed casually that morning, my tie hanging from my unbuttoned collar because I had the weekend off and was on my way to visit my Uncle Al in Rheims. The general stopped in his tracks and, in a commanding voice, asked, “What’s wrong with this picture, soldier?”

Bob, an amateur photographer and later a professional one, looked around and asked, “Picture, what picture?” in his decidedly New York twang. After which General Lee stepped in front of me, cinched up my tie, and returned my salute, exclaiming, “Now you look like a soldier!”

This was the same general whose headquarters initially insisted we stand reveille at 6 a.m. in the courtyards and streets of Paris. Our voices reverberated, prompting sleep-deprived Parisians to complain to the American military government and after a week or so, reveille was discontinued.

At one point, though, the real war nearly caught up with me. It was during the Battle of the Bulge, which began on December 17, 1944, when the U.S. Army was cut off during a desperate counterattack by the German army near Bastogne. This was the last-ditch battle by the Nazis in France.

American forces were badly outnumbered, but the commanding general, Brigadier General Anthony C. McAuliffe, famously responded to the German demand for surrender with the single word reply, “Nuts!” (a bit of American slang that proved a puzzlement for the Germans).

The GIs held out against overwhelming odds in one of the costliest and most heroic battles of the war. They finally broke through, but before the breakthrough, the situation was tenuous, and it looked as though the enemy and the cold might ultimately win out. There were nearly as many casualties from frostbite as from enemy action. It was also discovered that 84 GI prisoners of war were disarmed and summarily executed in a field.

Here’s how I came into the equation: The closest replacements were the headquarter troops in Paris, and the plan was to send those of us who were physically capable to the front. All personnel in the Com Z, S.O.S. Seine Section were ordered to report for a physical exam.

The call-up was alphabetical, starting from A to G. This placed me in the first group and I, once again, gave away my garrison equipment in view of my possible future.

I speculated that because of all the many times I had heard the phrase “kill or be killed,” my odds were, by definition, short.

When the orders were published, I couldn’t believe that my name was not on the list. Since then, when I’ve read accounts and seen movies about that horrific battle, I wonder, had I been selected, would I have survived? If so, would the horrors I’d have most probably seen haunt me for the rest of my life with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder? Which is the case with so many combat veterans.

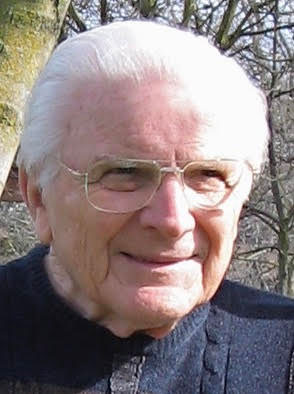

Mel Corren was born in Stockton in 1924, attended local schools, served in Europe during World War II, and after returning home joined his family’s furniture business, M. Corren and Sons. In 1961 he and his brother Hillard opened The Brothers, a home furnishing/design studio, which ran until they both retired in 2000. Mel, his wife Harriet, their two sons, two grandchildren, along with their respective mates, make up their far-flung family. His literary accomplishments are the memoirs “I’ve Live It, I’ve Loved It” and “Schoolboy, Soldier Boy”, both on Amazon, as well as a collection of short stories. At 96, he remains active in civic affairs, including his ongoing advocacy for the revitalization of Stockton’s historic downtown district. Mel was honored as Stocktonian of the Year for 2015.

- By Mel Corren

- August 17, 2022

- 9:37 pm

- No Comments

Leave a Reply