Stockton’s China Trade and Sperry’s Global Empire

- By Phillip Merlo

- Photographs by As Noted

- April 17, 2020

- 8:32 pm

- No Comments

Editor’s Note – This is the first in a series of SAN JOAQUIN STORIES produced by the San Joaquin County Historical Society and Museum

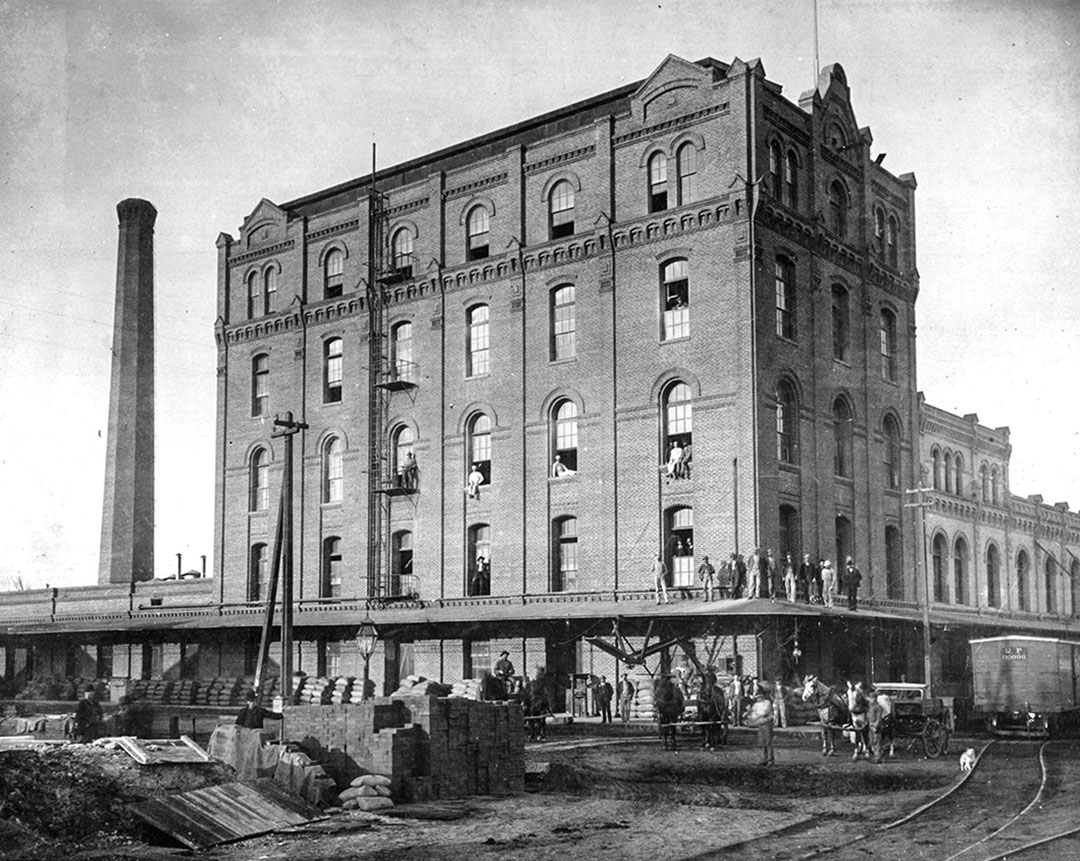

Many have heard of the once-great Sperry Flour Products. The old Sperry warehouse on the Stockton waterfront, an occupied ruin of the company’s past, stands on guard at the mouth of Mormon Slough in downtown Stockton.

Many essays and books cover the history of Sperry Flour Products in great detail. One story that has not been told, however, is the international importance of the company. The firm’s economic reach in the Philippines, China, Japan, Central America, and the UK solidified its role both as a primary agent of American imperialism, as well as a wellspring of financial and philanthropic investment during Stockton’s golden age of the early twentieth century. The thesis of this article is that Stockton-based Sperry Flour Products responded to local and international market conditions during the era of European imperialism to grow into a transnational firm, with trade networks penetrating across the globe. The mills on Stockton’s waterfront were the beating heart of a gilded age behemoth, responsible for much of San Joaquin County’s wealth in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The Foundation and Initial Growth of Sperry Mills: 1852-1873

Austin Sperry arrived in California in 1850, dreaming of fields of gold. He mined in the Mokelumne Hill area, reportedly earning $500 in five days before deciding against a permanent career as a miner. With a partner, A.W. Lyons, Sperry founded a grist milling operation in downtown Stockton in late 1852, at the time known as Sperry & Lyons Mill. Lyons left soon thereafter, and a number of partners came and went. In 1860, Austin’s brother Willard bought into the enterprise. From then on known as Stockton City Mills, the firm included the original Sperry Mill and the nearby Franklin Mill. (1)

Wheat agriculture first came to the Central Valley in 1856. Prior to this, grain was imported from Napa. The Central Valley proved ideal for wheat and barley, with the loamy soils surrounding Stockton providing particularly fertile grounds for farming. By 1867, approximately 1000 acres of land surrounding Stockton was involved in the growth of winter wheat, and between 1867 and 1871, 70,000 tons of flour were being produced on Stockton’s waterfront. By 1873, Sperry was shipping to the United Kingdom by way of San Francisco and Liverpool.

In 1881 Austin Sperry passed away. His brother Willard took command of the business. On April 2, 1882, a major fire destroyed the main Stockton City Mills plant along the waterfront. The firm lost between $120,000 and $150,000, with an insurance payment of $90,000 helping to recoup the losses. Undeterred, Willard immediately took a lease out for a grain mill in Lodi, and subsequently began the reconstruction of a new mill in Stockton. The new mill, named the Crown Mills, was finished on October 11, 1882, at a cost of $200,000. Local steam shipping baron and agricultural magnate J.D. Peters, known in the Italian community as Giuseppe di Pietri, named the mill. (2)

To understand Sperry’s resilience, it helps to examine the San Joaquin County economy at the time. By 1880, wheat and barley were the dominant crops of San Joaquin County and the Central Valley. To meet the demands of the grain farmers, local mechanical engineering firms such as Hickinbotham Brothers and the Holt Brothers Manufacturing Company were founded in the 1880s primarily to build grain harvesting equipment, such as threshers and combined harvesters. The demand for flour was so great, both in the American West and in the Pacific world, that much of the regional economy was organized into one supply chain.

At the same time, nature dictated that other types of agriculture were unprofitable. The great tributaries of the San Joaquin River– the Mokelumne, Calaveras, Stanislaus, the Tuolumne, and the Merced were prone to oscillating periods of drought and flood. (3) Central Valley farming communities did not possess irrigation systems to provide consistent water in drought years or consistent drainage in flood years. The Miller & Lux ranching partnership possessed a stranglehold on the irrigation rights to the San Joaquin River south of Lathrop, and the great California Delta was only in the infant stages of its reclamation. (4) The great dams of the Sierra Nevada had barely been conceived. In such conditions, dry-farming winter wheat and barley was the most stable, and hence profitable, agricultural enterprise available. (5)

Sperry’s Rise to Domination of the Pacific Grain Markets: 1870-1892

A variety of domestic and international factors allowed Sperry Flour Products to grow substantially in the 1880s and 1890s, to the point where it became the leading supplier of flour in the Pacific world. By the 1870s, the imperial powers of Europe had firmly solidified economic control of East Asia. The Opium Wars of 1839-1842 and 1856-1860 had dramatically weakened the commercial power of the Qing Empire in modern-day China. The island of Hong Kong, a Qing territorial concession to the British in the first Opium War, was made a duty-free port. Hong Kong, in addition to Singapore (a colony of the British since 1819), allowed for British merchant houses to expand their operations in China and Southeast Asia.

Other European states had already laid claims in Southeast Asia. The Philippines had been colonized by the Spanish as early as 1565, and were firmly entrenched as a colonial economy of the Spanish Empire. The Dutch crown had established dominion in Indonesia in 1800, and France would begin its colonization of Vietnam and Indochina in 1858. All of these European imperial ventures needed flour. This was in part to supply the needs of the European colonials, but increasingly by the 1880s due to local consumption. The culinary tastes of East and Southeast Asia were beginning to change, often due to the market pressures of imperial domination.

The example of imperialism in the Philippines is illustrative of the growth in flour consumption globally. In Daniel F. Doeppers comprehensive history of food in Manila and Luzon Island in the Philippines, Feeding Manila In Peace And War, 1850-1945, Doeppers chronicles the growth of flour as an essential product in Filipino cuisine. For most of recorded history, the cultures and societies of the archipelago had used rice as their primary foodstuff. After Spanish colonization, Catholic clergymen and Spanish colonial officials actively promoted baked flour goods, increasingly in the nineteenth century. By 1892, the archipelago was importing 7.4 million kilograms of flour annually. (6) In the 1870s and 1880s, virtually all of this flour was imported from San Francisco via duty-free Hong Kong, and much of it carried the Sperry brand, with Stockton, California proudly labeled on the sacks. (7)

By the late 1880s, Sperry Flour possessed a virtual monopoly on flour products sold in much of the Philippines. (8) The most popular product was the XXX label, variously marketed as Drifted Snow (US markets), the Green Girl (UK, Dutch, and Chinese markets), and Senorita (the Philippines and Central America). (9) Products were imported to the Spanish Philippines and the rest of Southeast Asia by British firm Warner, Blodgett & Co, later known as Warner, Barnes, & Co. By the 1880s the Sperry family had grown the Stockton City Mills into a solidly transnational firm. In addition to the Spanish Philippines, one could purchase Sperry flour brands in Singapore, South China in Guangdong province, the Dutch East Indies, and even Australia. Elsewhere globally, Sperry was sold in Mexico, El Salvador, Panama, the United Kingdom, and the Russian Empire. (10)

Economies of Scale and the Consolidation of the Market: 1892-1905

Wheat production in California and San Joaquin County peaked in the early 1880s. In the banner year of 1880, just prior to the Sperry fire of 1882, California exported 1,626, 868 tons of wheat product. Exports to Great Britain and Western Europe represented the vast majority of this trade, but in 1885 China still purchased 437,471 barrels of flour, and Japan, Mexico, Russia, and the Philippines were all stable customers. (11)

The 1890s saw increasing competition in the flour economy. In 1892, increased flour production in India and Argentina lowered the global price of both flour and grain. Local competition with Oregon and Washington State firms further caused profitability to decline. To address these threats to business, in 1892 Sperry would swiftly merge with several other California milling companies, notably the Davis and Golden Gate Mills owned by Horace Davis, in a successful bid to corner the regional grain industry. The corporate headquarters would be moved to San Francisco, with production and supply chain management based in Stockton.

In an 1892 article in The Evening Mail of Stockton, George Sperry explained the rationale behind the merger. The overproduction of wheat globally was driving prices down, and competition with Oregon was viewed as a serious threat. The historical data shows he was right. In 1880 flour sold for $1.47 per cental. (12) By 1890 prices were down $1.25 per cental, and in 1894 prices were down to 90 cents per cental. (13) The new entity, Sperry Flour, Inc., was able to offset these price declines by consolidating operations and maintaining targeted marketing campaigns in its Asian markets. The firm also later added the Union Mills of W.B. Harrison to its corporate holdings, in 1896 and from that point forward, from the standpoint of production, California effectively became a one-flour company state. The new company was large enough to outcompete its rivals in the Pacific Northwest.

Foreign demand for Sperry Flour products remained high, post-consolidation. In 1900, newspaper reports show that the company was sending steamships from San Francisco to Hong Kong, Shanghai, Yokohama, Honolulu, Puerto Vallarta, and Liverpool. The Warner, Barnes & Co. imports offices in these cities were some of the highest revenue trade offices in the world. In Manila, in the wake of the Spanish-American War and subsequent American War of Colonization in the Philippines, Sperry Flour Products became a major purveyor of US goodwill. The C. Lutz & Co groceries warehouse used the purported superiority of Sperry Flour to help justify the imperial takeover of the archipelago to disenfranchised Filipinx communities of Luzon and Cebu. (15) Only a year or so later, Sperry would again be in the international headlines. In December of 1903, mills owned by the Sperry Flour, Inc. conglomerate shipped nearly a year’s worth of flour to Yokohama, Japan, to supply the Japanese military in its upcoming war with Russia. (16) Flush with cash, Sperry Flour was able built a massive warehouse facility on the Stockton waterfront during this time period that stands to this day – the notable Waterfront Warehouse on Weber Avenue.

Decline in California Wheat Agriculture and the Stockton Operation: 1905-1929

Despite its best efforts, Sperry Flour, Inc., a pioneer in wheat mechanization and global wheat sales along the Pacific Rim, could ultimately not contend long-term with the decline of wheat production in California. In 1906 the slow decline of wheat production in the Central Valley experienced a massive acceleration. As the once fertile loam soils were becoming exhausted of nutrients, a simultaneous expansion of orchard, vine, and vegetable crops began in San Joaquin, Stanislaus, and Merced counties, largely as a result of increasing access to irrigation and the tractor-mechanics innovations of Holt Manufacturing Company. In that year, less than five hundred acres of the entire California wheat crop were harvested. (17) Wheat agriculture in California never recovered. Until the 1970’s, never more than 1500 acres of the crop were harvested. Sperry Flour Products, Inc. was forced to import wheat from Oregon, Washington, Kansas, and increasingly Australia and Chile to achieve its production goals, and in 1915 actually went so far as to develop a laboratory farm in concert with the University of California to experiment with new farming methods – such was the dire need for wheat. (18) On November 25, 1915, the Sperry Flour Products company pleaded in The Stockton Daily Evening Record for San Joaquin County farmers to innovate with new production methods, noting Sperry’s role in the local community. (19) These efforts were relatively unsuccessful. In July of 1917, G.W. Hamilton, Manager at Sperry’s Paso Robles Mill, wrote of California wheat that the “the quantity now grown is relatively negligible and the quality alarmingly inferior.” He noted that mills at that point could only use twenty-five percent California wheat, relying on imported grain from other states. (20) In August, W.L. Reedy of the San Francisco Office of the firm, noted that the 1917 wheat crop in California would not be “sufficient for local requirements.”(21) The company began to rearrange its production chain, with a Sperry facility in Spokane built to accompany a Tacoma plant, reflecting the increasing role of the Pacific Northwest, and the low yield of California production.

As California grain agriculture declined, Sperry’s global supply chain faced multiple shocks. A boycott in China in 1905 of American products in response to Theodore Roosevelt’s Open Door Policy opened the door for the Hong Kong Milling Company to completely take away Sperry’s market share in Southern China, and the growth of milling operations in Australia slowly siphoned away business in Indonesia and Singapore. In Central America, Chilean wheat shipped from Valparaiso also gained market share. (22) Sperry maintained large profit margins, but only through an increasing reliance on cheap wheat produced outside of California. (23)

On January 1, 1926 the firm moved its milling headquarters from Stockton to Vallejo, largely to be closer to the trade and shipping office in San Francisco, which grew in importance for the firm as local wheat production declined. The lack of a deep water channel to the bay, which would not be built for another five years, was the primary cause of the move. The company had acquired major debt in the construction and acquisition of its mills in the Pacific Northwest and around California in the 1910s, and the firm ultimately merged with General Mills in 1929. (24) Sperry continued as an incorporated brand of General Mills until 1952.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of Sperry Flour Products in the history of San Joaquin County and Stockton. The firm put Stockton on the map as a major producer of commodities, and was instrumental in mobilizing the mechanical engineering industry in the area to innovate – playing a key role in the rise of Holt Manufacturing. The profits reaped through sales to China, the Philippines, and elsewhere were invested locally in employee incomes, stakeholder investments in local banks (including the infant Bank of Stockton, then known as Stockton Savings and Loan), and in philanthropic dollars. One sterling example of this is that Mary Elizabeth Simpson Sperry, the widow of founder Austin, was the largest donor to the Stockton Equal Suffrage Club during the successful campaign of 1911. (25) The international Sperry empire was critical in making the Greater Stockton region an industrial powerhouse in the late nineteenth century, squarely putting Stockton on the global map.

END NOTES

1 Renee McComb. “The Sperry Flour Mills of Stockton.’ San Joaquin Historian. Volume 3, New Series, Spring 1989.

2 Ibid.

3 For more information on flood and drought patterns in Central Valley rivers over the past two hundred years, see Paulson, R.W., Chase, E.B., Roberts, R.S., and Moody, D.W., Compilers, National Water Summary 1988-89– Hydrologic Events and Floods and Droughts: U.S. Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 2375.

4 An excellent modern-day analysis of the role of Miller & Lux in dictating the Central Valley economy’s fortunes can be found in Chapter 2 of Tim Stroshane’s Drought, Water Law, and the Origins of California’s Central Valley Project, published in 2017 by the University of Nevada Press.

5 For data on the milling operations in Stockton and wheat harvest statistics in San Joaquin County at this time, view the daily “Commercial Notes” articles of the Daily Evening Herald from August 1881. One can also use US Agricultural Census data to view the rise of wheat in proportion to other crops in the nineteenth century. Access information in the search bar at census.gov.

6 Doeppers, Daniel F. Feeding Manila In Peace And War, 1850-1945. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. See pages 279-287 for detailed information on wheat consumption and imports in the Philippines.

7 Daniel Meissner. “Bridging the Pacific: California and the China Flour Trade.” California History 76, no. 4 (1997): 82-93. Accessed April 13, 2020. doi:10.2307/25161678.

8 Ibid.

9 “A Chat About Flour.” The Daily Evening Mail, September 1, 1892.

10 Meissner. Extensive records of Sperry flour sales exist in colonial trade journals across the Pacific rim, including The Hong Kong Government Gazette, British Consular Reports, El Commercio in the Philippines, and many others.

11 See the National Agricultural Census from 1880 for total wheat exports data. See Doeppers for information on flour exports to various countries.

12 A cental is an archaic unit of weight equal to 100 pounds.

13 Horace Davis. “California Breadstuffs.” Journal of Political Economy 2, no. 4 (1894): 517-35. Accessed April 14, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/1829739.

14 Meissner.

15 See articles in the Philippines business paper El Commercio from 1902-1905 for detailed examples of foreign trade firms using Sperry Flour products and other American products in ways evidently used to rationalize American colonization. Trading houses would associate Sperry products with American industrial power.

16 San Francisco Chronicle. December 31, 1903.

17 USDA/NASS. Quickstats. Available online at: http://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/ (Accessed 4/14/2020)

18 The Sperry Family. November, 1915. The Sperry Family was the company’s newspaper.

19 “Sperry Flour Company Desires To Patronize San Joaquin Farmers.” Stockton Daily Evening Record. November 15, 1915. This article implicitly stated that declining wheat production could end Sperry’s existence in the city.

20 G. W. Hamilton. “Can California Wheat Come Back?” The Sperry Family. July 1917.

21 W.L. Reedy. “The Wheat Crop in California.” The Sperry Family, August 1917.

22 Meissner. For an authoritative treatment of the rise of Chinese wheat industry in the first decade of the twentieth century, largely in patriotic reaction to American imperialism in Asia, see Meissner’s monograph: Daniel J. Meissner. Chinese Capitalist versus The American Flour Industry, 1890-1910: Profit and Patriotism in International Trade. London: Edwin Mellen Press, 2005.

23 “Sperry Flour Reports Big Profit.” San Francisco Examiner. August 17, 1915.

24 “Flour Company Acquired.” The New York Times. March 1, 1929.

25 See the papers of Minerva Goodman, at the Holt-Atherton Library, for information on Mary Sperry’s contributions to the Stockton Suffrage movement.

Phillip Merlo serves as the Executive Director of the San Joaquin County Historical Museum. He previously taught History at Franklin High School in Stockton. Phillip works with local nonprofits, Stockton Cultural Heritage Board, and as a Trustee of Little Manila Rising. He strongly believes in using history and education to make the world a better place.

- By Phillip Merlo

- Photographs By: As Noted

- April 17, 2020

- 8:32 pm

- No Comments

Leave a Reply