Homeland Defense

Cucunuchi (Estanislao) and the Native Freedom Fighters

The California heartland produced one of the continent’s greatest Native American leaders, prominent among the multitudes who fought to protect traditional homelands and lifeways. A California Indian man, Cucunuchi, who was called Estanislao by the Spanish, led Native freedom fighters from the southeastern San Joaquin Delta and northern San Joaquin Valley in military battles against the largest colonial army assembled in California before it became part of the United States.

Researcher Sherburne Cook said that “Estanislao belongs with King Philip [Metacomet, from Massachusetts], Tecumseh, Pontiac, and Geronimo, as an outstanding Indian chief who fought the white man with persistence and daring. …by far the most able military and political leader produced by the [Indians] in California.” 1

For an overview of the lifeways of the Native Americans who lived on the east side of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, see a prior Soundings article, “Deep History of the Delta.” That article also sketched some of the resistance by Delta Indian nations against the Spanish/Mexican colonial encroachment crossing the Coastal Range into the heartland. This article is an account of the most intense of those resistance battles, sometimes called Estanislao’s Rebellion.

The homeland of the sovereign, Yokuts-speaking Lacquisemne nation was along the lower Stanislaus River (near the modern city of Ripon). In 1820-23, many of the Lacquisemne succumbed to the pressure of Spanish mission fathers and the army that accompanied them and moved to Mission San José (in present-day Fremont, about fifty miles west-southwest).

On September 24, 1821, Father Buenaventura Fortuni baptized a twenty-eight-year-old Lacquisemne man named Cucunuchi and assigned him the name of Polish Saint Stanislaus Kostka: “Estanislao” in Spanish. Cucunuchi’s twenty-two-year-old wife Youatae, toddler daughter Lanucuye, and his fifty-year-old mother Pitzenete, were also baptized at that time. His father, Sucais, remained in their Stanislaus River homeland. Estanislao was a good vaquero (cowboy) and mule breaker, he learned to speak and perhaps read Spanish, and eventually became an alcalde (foreman of Indian workers) at Mission San José.

Mexico gained independence from Spain and adopted a new liberal constitution in 1824. The Mexican governor of California, José María de Echeandía, issued an order to emancipate mission Indians who were qualified for Mexican citizenship. Change had begun, even though freeing the mission Indians and secularizing the mission churches would not happen for another decade or more.

A couple years after the switch to Mexican rule, American trappers—the first to enter California from the east, led by Jedediah Smith—defied Mexican orders, entered Lacquisemne territory, and spent the summer bivouacked on the Stanislaus River. “Smith’s presence in the Central Valley and good relations with the…Indians soon generated problems for the missions and [Mexican] government authorities along the coast.” 2 At minimum, the lack of a vigorous Mexican military response to the American trespassers gave mission Indians hope in fighting for their own freedom. A few months after the Smith party departed California, large numbers of Yokuts-speaking Indians originally from the lower Stanislaus River left the coastal missions and returned to their homelands.

Mission Indians had suffered extremely high death rates and steeply declining populations—primarily due to European diseases and unhealthy living conditions at the missions. They were forcibly detained and confined at the missions, were often severely punished, and were toiling in a “semi-slave and semi-feudal system built on Indian labor in the present and [the promise of] otherworldly salvation sometime in the future[-–thus] there were ample reasons for native people to be restive. This was especially true for the Yokuts, who came from far away and who…had the option of returning to their home villages and prior lifestyle.” 3

In 1828, several hundred Lacquisemne Indians from Mission San José and significant numbers of other Yokuts-speakers from Mission Santa Clara de Asís fled and formed a multi-national refugee band on the lower Stanislaus River. Others came from Missions San Juan Bautista and Santa Cruz. A common enemy for these freedom fighters was the coastal Hispanic slave-raiders that continued to ravage Native communities. Horses had become abundant and provided the Indian patriots with meat, quick transportation, and a resource that could be traded.

At the same time as they were acquiring horses, the Indians of the Central Valley were also becoming more knowledgeable about [Mexican] fighting tactics…Along the whole frontier, mounted Indians were preparing themselves for increased warfare…more than anything else,…to prevent Hispano-Mexican expansion into the interior of California. 4

Estanislao was a charismatic leader of a resistance group comprised of as many as two thousand freedom fighters. Another key leader of the Indian patriots was Huhuyut, who had been renamed Cipriano at Mission Santa Clara de Asís on May 6, 1815. Cipriano was from the Yokuts-speaking nation downriver from the Laquisemne, the Josmite (also called the Pitemas). He may have been related to Estanislao by marriage. Estanislao’s brother, called Sabulon, was also an important leader.

Estanislao sent a message to Father Narciso Durán of Mission San José, who was the Franciscan Father-President of all the California missions, that the Native people were rising in revolt and would defend their homelands. They occupied most of what is now southern San Joaquin and northern Stanislaus counties, actively raided Coastal Range ranchos, and encouraged Indians to leave Missions San José, Santa Clara de Asís, Santa Cruz, and San Juan Bautista.

The livestock-stealing raids upon missions, ranchos, and pueblos (towns) were characterized by stealth and trickery; citizens were seldom injured. Estanislao sometimes carved his initial to let people know who was responsible, thus he is thought to be one of the inspirations for the fictional character, El Zorro (The Fox).

Father Durán in November 1828 requested military intervention in response to the raids, directing that “Everything depends upon capturing dead or alive a certain Estanislao from this mission and a person from Santa Clara called Cipriano.” 5 Estanislao and Cipriano prepared for the confrontation by putting out a call to arms to Native patriots in the Central Valley.

Soon there was a skirmish along the Stanislaus River between the Native freedom fighters and fifteen Mexican soldiers from the San Francisco presidio, under the command of Sergeant Francisco Soto. Accounts of this confrontation are sketchy because the sergeant was wounded in the exchange and died shortly thereafter. The Indians apparently taunted and lured the hot-headed Soto into their chosen battlefield and killed two or three soldiers and wounded four to six others before the Mexicans retreated to the coast.

More fully documented was a subsequent Mexican expedition, after the rainy season, in early May 1829. Forty soldiers from the San Francisco presidio, plus about seventy Indian militiamen from Mission San José, led by an experienced Indian-fighter, Sergeant José Antonio Sanchez, were sent to apprehend Estanislao and his followers. The rebel band was holed up in the dense riparian forest “jungle” along the Stanislaus River, probably somewhere near present-day Riverbank or Oakdale, although some researchers have located the battle site as far downriver as Caswell Memorial State Park. The Native patriots had constructed elaborate defensive structures, perhaps modeled after or repurposing barricades made by Jedediah Smith’s American trappers. “The Indian stockade on the Stanislaus River was astonishing: a palisade of split stakes, in the recollection of one Mexican soldier who confronted it. Parapets of thick, strong timbers interlaced with trenches, in the memory of another.” 6

Sergeant Sanchez had intended to bombard the Indian rebels, but a broken carriage on the artillery piece rendered it useless. Infantry tactics proved ineffective against Estanislao’s defensive works. After two full days of fighting, the Mexican forces had not driven the Indians out of the stronghold and had suffered two dead and nineteen wounded. Sanchez abandoned the siege and withdrew from the victorious Indian freedom fighters, arriving at Mission San José on May tenth.

This victory by the Native patriots over Mexican regular forces and militia was a milestone in large-scale armed resistance among California Indians. It was the first substantial Indian victory over the invading Spanish or Mexicans. It was also noteworthy because the Indian fighters included individuals originally from many Native nations, dialects, and languages in the San Joaquin Valley, Delta, and the lower Sacramento Valley—perhaps even Chumash-speakers from the Santa Barbara coast who had fled to the tulares (Central Valley tule marshes) after their 1824 revolt at Missions Santa Inéz, La Purísima Concepción, Santa Bárbara, and San Buenaventura. Moreover, the Native patriots effectively countered European battle tactics and used defensive earthworks, trenches, and barricades to defend their homelands.

The Mexicans had to retaliate. Commander Ignacio Martínez wrote to twenty-two-year-old Alférez (second lieutenant) Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo at Monterey:

The Indian rebels from Missions San José and Santa Clara have gathered together at the rivers, resolved to die rather than surrender. They are extremely insolent…, seducing the other [Indians] to accompany them in their evil and diabolical schemes, openly insulting our troops and ridiculing them and their weapons. …[Y]ou will proceed to these rivers with all the troops [available]. …The objective will be to administer a total defeat to the…Indians…, leaving them completely crushed. 7

Troops were drawn from the presidios at Monterey and San Francisco to comprise a force of 107 soldiers, some citizens, and at least fifty mission Indian militiamen, equipped with a cannon and carrying 3,500 musket rounds—the largest army ever assembled in Hispanic California. Sergeant Sanchez, who had led the prior campaign and knew the terrain and the Indians’ tactics, was Vallejo’s second-in-command.

The formidable force left Mission San José and descended into the San Joaquin Valley near Laguna del Blanco, not far from present-day Tracy.

Having crossed the San Joaquin River by means of rafts on May 29th, [1829] the army arrived the next day at the scene of the former battle, where they were met as before by a cloud of arrows. The wood was found to be absolutely impenetrable, and Vallejo at once caused it to be set on fire, stationing his troops and his three-pounder [cannon] on the opposite bank of the river. The fire brought the Indians to the edge of the thicket, where some of them were killed. [Late that afternoon, twenty-five soldiers in thick leather jackets, collars, and helmets were sent to attack] the foe, and fought over two hours in the burning wood, retiring at dusk with three men wounded.

Next morning at 9 o’clock Vallejo with thirty-seven men again entered the wood. He found a series of pits and ditches arranged with considerable skill, and protected by barricades of trees and brush. Evidently the Indians could have never been dislodged from such a stronghold except by [fire]. …The enemy, however, had taken advantage of the darkness of night and had fled. Vallejo started in pursuit. He camped that night on the [Stanislaus River] and next morning surrounded a part of the fugitives in another thicket near their [village]…. The Indians declared they would die rather than surrender, and late afternoon the attack was begun. A road was cut through the [brush] with axes, along which the field-piece [cannon] and muskets were pressed forward and continually discharged. The [Indians] retired slowly to their ditches and embankments in the center, wounding eight of the advancing soldiers. When the cannon was close to the trenches the ammunition gave out, which fact, and the heat of the burning thicket, forced the [soldiers] to retreat. During the night the besieged Indians tried to escape one by one, some succeeding, [others] being killed. Next morning nothing was found but dead bodies and three living women. That day, June 1st, at noon, [ammunition and] provisions being exhausted, Vallejo started for San Jose, where he arrived on the fourth. 8

Vallejo allowed his forces to execute the three captured women in the field. “Children [from area villages] were spared such deaths. They were more valuable alive. Vallejo’s soldiers captured many, herding them…to the mission and the presidios, where they were distributed as servants and slaves.” 9

Although Father Durán complained to Governor Echeandía about Vallejo’s barbarous murder of the captured Indian women and the “harvest of children,” Vallejo was exonerated. He rose to hero’s prominence and received a 66,600-acre land grant, Rancho de Petaluma (see Petaluma Adobe State Historic Park).

Estanislao returned to Mission San José shortly after the battle and asked Father-President Durán for forgiveness. The Father successfully petitioned the Mexican governor and a pardon was granted to Estanislao and his men in October 1829. Estanislao went underground, moving between the mission community and his Stanislaus River homeland, and apparently continued raiding. He is thought to have died at the mission on July 31, 1838, perhaps of smallpox or malaria.

The Stanislaus River and Stanislaus County were named in honor of the Indian patriot Cucunuchi, albeit with his Anglicized Christian name.10

The valley Indians were fighting the Mexican Californians to a standstill, making their lives intolerable with incessant raids upon ranches and missions. What would have been the outcome, no one can tell, for a third element was already making its weight felt, the Anglo-Americans who came now, by 1841, pouring in a never-ending stream onto the Pacific Coast. Both Indians and [Mexican] Californians were submerged and obliterated by the flood, and the[ir] fate [was] determined by the new invaders. 11

Some of [Estanislao’s and Cipriano’s] recruits became well-known native leaders in their own right…[including] Yozcolo, a [lower Stanislaus River] Yokuts alcalde from [Mission] Santa Clara [whose severed head the Mexicans displayed on a pike at that mission in 1839]. A rebellious Miwok alcalde from Mission San José, José Jesús, would also take up horse raiding in the valley of the San Joaquin. He proved to be a remarkably resourceful leader who would help shape events in the interior until the 1850s. 12

NOTE: This article is based on the author’s research for a chapter in: “The Native Peoples of San Joaquin County: Indian Pioneers, Immigrants, Innovators, Freedom Fighters, and Survivors,” Part Two, The San Joaquin Historian, winter 2016, published by the San Joaquin County Historical Society.

Endnotes

- Sherburne F. Cook, “Expeditions to the Interior of California, Central Valley, 1820-1840,” University of California Anthropological Records 20, No. 5 (1962), p. 165.

- Shoup, Laurence H. and Randall T. Milliken, Inigo of Rancho Posolmi: The Life and Times of a Mission Indian (Novato, Calif.: Ballena Press, 1999), p. 88.

- Shoup and Milliken, Inigo, pp. 87-88.

- Jack D. Forbes, Native Americans of California and Nevada: A Handbook (Healdsburg, Calif.: Naturegraph, 1969), p. 35.

- Cook, “Expeditions to the Interior of California,” p. 169.

- Thorne B. Gray, The Stanislaus Indian Wars: The Last of the California Northern Yokuts (Modesto, Calif.: McHenry Museum Press, 1993), p. xxv.

- Martínez quoted in Cook, “Expeditions to the Interior of California,” pp. 175-76.

- Herbert H. Bancroft, History of California (San Francisco: History Company, 1886-90), vol. 3, pp. 112-13.

- Gray, The Stanislaus Indian Wars, p. 61.

- In 2001, a beautiful statue of “Chief Estanislao” was installed outside the Stanislaus County Superior Court building in Modesto; it was sculpted by Betty Saletta and donated by the Tony Mistlin family of Ripon. Unfortunately, the statue depicts the California Indian as if he was from the Great Plains, wearing only a loincloth, with long thin hair, and no facial hair. There are no known photographs or other portraits of Cucunuchi-Estanislao, although he was repeatedly described as tall, lean or muscular, with thick hair and a heavy beard. He would have worn mission-era cotton or wool trousers and shirt.

- Cook, “Expeditions to the Interior of California,” p. 193

- Albert L. Hurtado, Indian Survival on the California Frontier, Yale University Western Americana Series, No. 35 (Binghamton, N.Y.: Vail-Ballou Press, 1988), p. 43. Yozcolo often wore a mask when raiding, perhaps another inspiration for the character El Zorro. An alliance between Charles Weber and José Jesús allowed Weber to settle and develop his Mexican land grant in what became at statehood San Joaquin county and to establish what became the city of Stockton, which in the early 1850s was the third largest city in the new state. José Jesús provided Native laborers to the Stockton Mining Company—the first such company in California, founded by Weber and several partners shortly after the initial gold strike in 1848. The chief also enlisted Native fighters and joined the California Battalion, led by U.S. Army brevet lieutenant colonel John C. Frémont in the Mexican-American War.

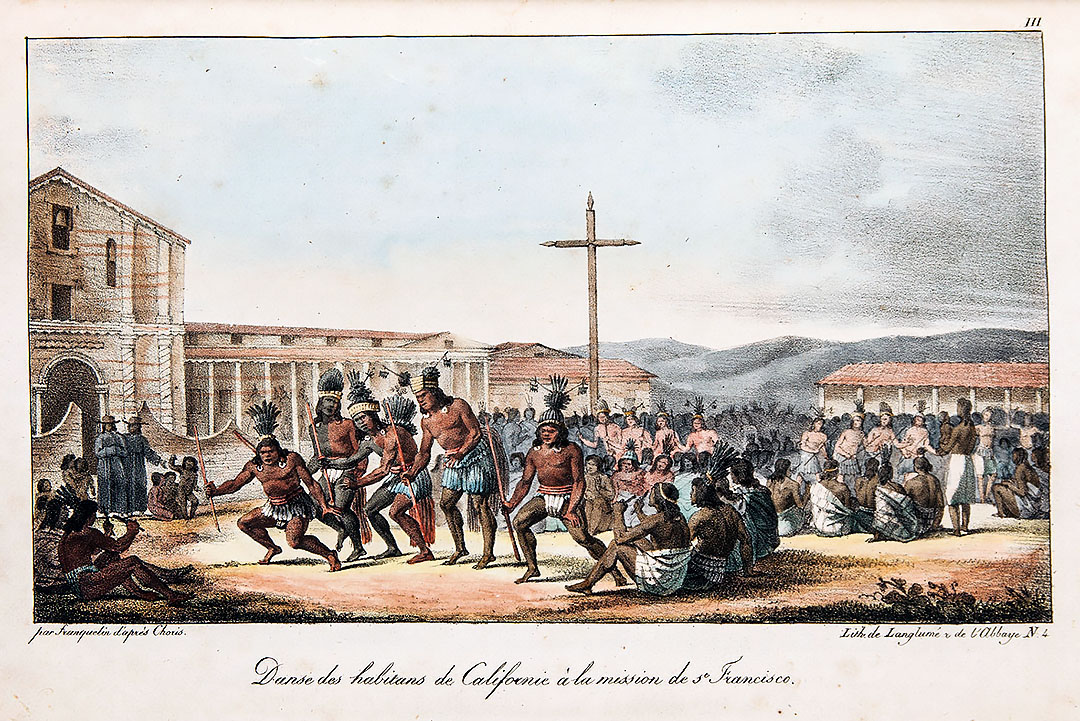

Ludovik (Louis) Choris (1795-1828) provided some of the most beautiful and accurate images of early California. The Russian artist visited California in 1816 with the Kotzebue Expedition and published a book of lithographs in 1822: Voyage Pittoresque autour du Monde.

David Stuart recently retired as the executive director of the San Joaquin County Historical Society. Previously, he directed the Sacramento History Museum, the Sacramento Science Center, and museums in Ventura. His family settled in the Delta in 1860.

Leave a Reply

4 Comments

I read this with great interest and appreciate the clarity of your writing. That must have been a trying time, when the scale of change and opposition of beliefs likely made trust of the “other” next to impossible. I am guessing that clear communication between clashing groups was rare. The story is tragic.

Thank you, Phoebe. Thoughtful comments.

Thank you for setting the record straight.

Thanks, Cyndy!