Closeup: David Webster Smith

Tugboat Engineer with an Artist's Eye

- By Laura Paull

- Photographs by David Webster Smith

- 2 Comments

It might be mid-morning, when the sun finally breaks through the diffused glow of the San Francisco Bay fog. Or it might be at sundown, the encircling hills awash in rose gold, or in the spotlight of a bright moon, that the big ships glide into port: container ships piled high with boxcars, bulk ships loaded with gypsum, oil tankers heading to or from the Chevron Long Wharf or Benicia, at the mouth of the California Delta. Tugboats, dwarfed by the massive ships, guide the throbbing giants to safe port or out to sea, their crew scanning the ships’ hulls for countless functional reasons.

Then the tugboat engineer might notice, with another eye not related to his job, that a particular conformation of scratches, dents, and rust spots on the side of a particular ship looks kind of like a seabird in flight. Or a whirling sandstorm. Or, simply: beautiful. But only up close. He raises his camera with the 400 mm lens. “Click.”

Another potential masterpiece of abstract art.

David Webster Smith is that most rare of artists: one with a union “day job” that actually brings him closer to the creative work he loves. As a tugboat engineer and deckhand for Baydelta Maritime, a two-tug company, he works a seven-day week on board the Bay Billie, alternating with a week off. During his stints on the tug, he’ll do six hour shifts, interspersed with free time to look at the Bay in all its variances, roam with his camera, or sleep. He spends that free time with purpose, now that he knows what he’s looking for.

About eight years ago, after three decades working as a solo commercial fisherman along the coast from Monterey to Westport, Washington, Smith leveraged his boating experience and the hours he’d logged at sea to certify for the job. He had married a woman who shared an interest in Costa Rica, a travel writer named Erin Van Rheenen. The erratic hours of a fisherman’s lifestyle did not complement married life, even at its most liberal. “You follow the fish, you never know where you’re going to be, or when you’re going to be home.” Tugboat work was steady, a good solution.

Smith had been shooting, in an unassuming way, for at least a dozen years before he set foot on a tug. Fond of street photography, he would carry a small camera when travelling in Costa Rica, or wandering San Francisco, as so many aspiring photographers have done. The Bay also called him, visually, and his photographs, mostly black and white, of things seen upon the waters and great docked ships under moody skies, reveal a compelling sense of place. These works were a prequel to the art that would come to define him.

As he tells it, soon after starting the tugboat gig, he was developing some photos at a lab in the city called Dickerman Prints, when he spied a stack of large format prints of ships. Enquiring about the photographer, Jan Tiura, he learned that she was the first female tugboat captain in the San Francisco Bay, and had even worked a few years for Baydelta Maritime. What captivated Smith was that, with very basic equipment, she had focused on visual details that completely changed one’s perspective of the subject.

“She described ships as ‘a big painted box,’” Smith recalls. “Her work intrigued me and gave me the impetus to start really studying the ships up close. I realized that I had the access, and the imagination, to do something very different. It’s not many photographers who can get as close to big ships as I do.”

At that time, he didn’t have the distance lens he needed, so he would shoot from the tug when the ship was close, sometimes 5 to 10 feet away. “That limited the perspectives I could get,” he says.

Today, shooting with a small-bodied Fuji X-T2 (a mirrorless camera), usually with a 100-400 mm lens (which translates to 200-600mm lens in a regular format camera) he can obtain tight shots of sections of ships that are still quite a distance away — even when they are moving.

Commercial ships — “the largest man-made things that can move,” as he notes on his website — are not innately beautiful. But that is not the way Smith sees them.

“I look at ships as abstract canvases — and it was the camera that really made me see this,” he says. “Until they get weather worn and beat up by the sea and environment, they are kind of uninteresting — just a wall of fresh paint. But over the years they get character scars. Like a whale. They tell their own story.”

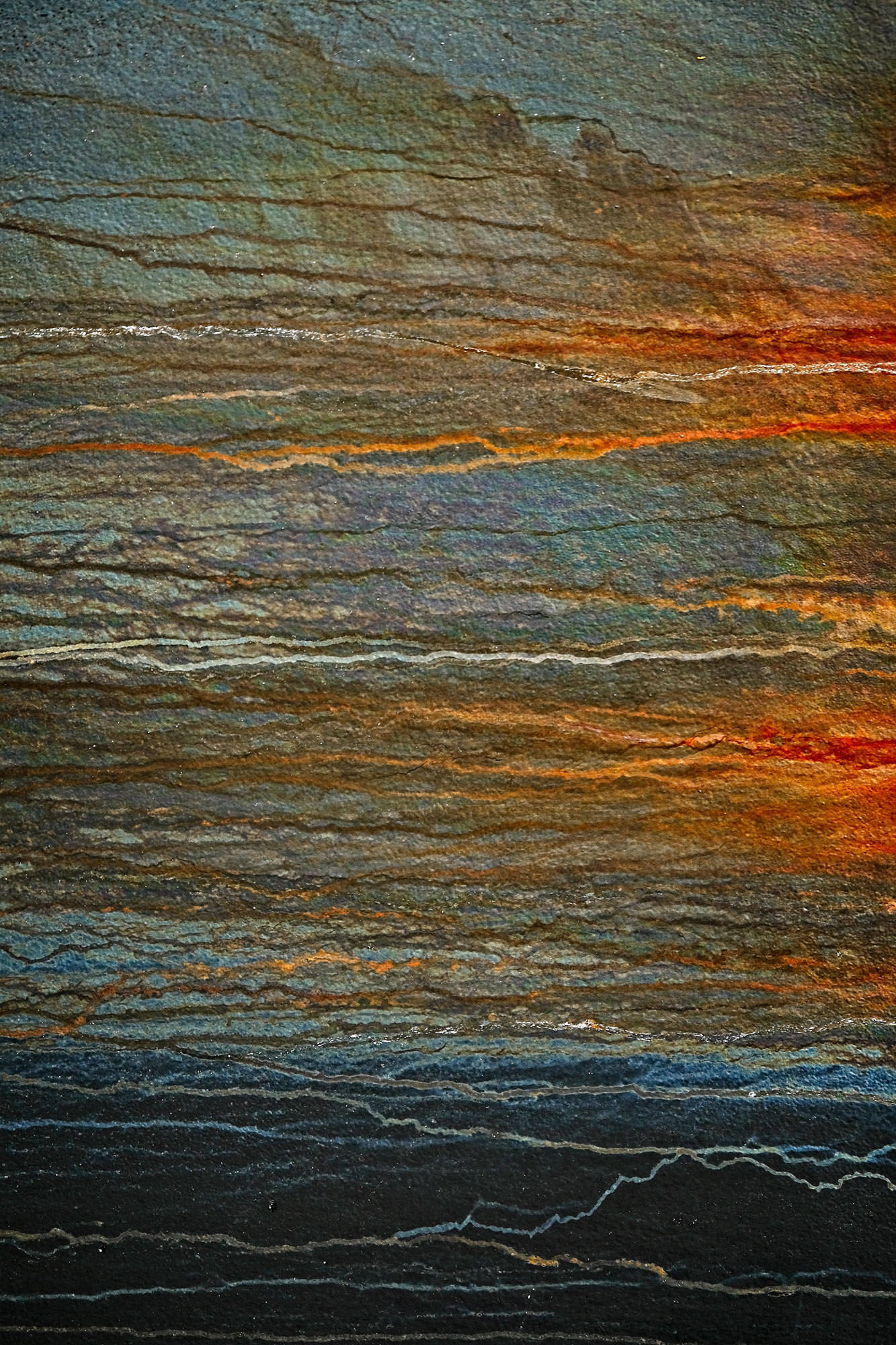

Those sea tales are secrets the ships keep. It takes an artist’s imagination to see something in the “scars” that hint of voyages past. Take, for instance, the image he calls “Oxidized Hieronymus” — referring to the 15th century Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch. For Smith, the dents and degradations this hull endured have produced a canvas of orange-tipped, ghostlike figures flying across a slate blue field, suggesting a Bosch-like landscape of infernal activity.

Or “Climate Change,” which also captures the vivid browns and oranges of rust scoring a blue-gray hull. Shooting in diagonal trajectories like asteroids or missiles above a leaden sea, they suggest a past – or future – apocalypse.

Yet others, such as “Rothkoesque,” a study in fields of blue evocative of its painterly namesake, lean toward the purely abstract.

His titles are suggestions only, of course, often using Spanish words that seem to be part of his intimate vocabulary. “Zacate” — Spanish for ‘hay’ — features a repetitive pattern of cream-colored marine grass sprouting from a deep burgundy hull. Haphazard beauty is clearly in the beholder’s eye.

Many of his photographs find creatures in the blotched and layered paint — a maritime form of cloud-gazing. In “Caballito” he sees a horse’s face amid the muddled, layered colors of the weathered ship.

“I find I’m drawn to marks on the ships that remind me of birds, or landscapes, or fish,” he admits. “It seems that all the details that I like recall some part of the natural world.”

Top left: Oxidized Hieronymus, Top Center: Caballito, Top right: Puerto Azul, Bottom left: Otromundo, Bottom Right: Climate Change

The ‘natural world’ is ever present for Smith, even as he wrestles with the mechanical activity of commercial ships. Besides his three tugboat mates, fish, seabirds and marine mammals are his constant companions out on the water. “It’s good to see that the marine life is not extinguished by all the traffic on the Bay,” he reflects.

But he can’t help but be acutely aware of air and water quality — and not only because “bad air days” provide poor visibility for photography. He witnessed the black smoke from the 2012 Chevron Refinery Fire in Richmond, spreading for miles, as he was coming in under the Golden Gate Bridge. He is uneasy about the foreign ships loading coke – a high carbon coal byproduct – from the Benicia docks, leaving a fine black film upon the water that eventually sinks to the bottom.

“It’s something people need to be aware of, and cautious of,” he warns. “Actually I think things are better regulated now than they were a few decades ago — and for good reason.”

In the full fervor of the photographic interest he’s discovered, Smith takes hundreds of shots every week on the water, and spends countless hours processing them back on dry land. Galleries are beginning to recognize the value of this interface between Smith’s vocation and his extraordinary vision: his photo, “Climate Change” won the top prize and an Award of Excellence in a group show, “Purely Abstract,” at the Healdsburg Center for the Arts last spring. And he recently garnered a Silver Medal at the juried San Francisco Bay International Photo Show at the ACCI Gallery in Berkeley, among other exhibitions. He’s driving at larger format prints with ever greater abstract detail — and apparently there is no dearth of unique color formations on the hulls of ships.

“Part of my drive as an artist, I think, comes from knowing I’m in the belly of the industrial beast,” he reflects. “Part of me wants to escape that, though of course I like my job and the people I work with. And they are amenable to what I’m doing. They’ve started to be my scouts. ‘Hey,’ they’ll say. “You should go check out this boat I saw.” We’re all looking for the art on ships now. It’s fun.”

Laura Paull has been writing since childhood and has yet to run out of subjects for her stories. A New Yorker by birth and Californian by choice, she is drawn to water, and when living in the Central Valley for many years would take frequent trips to explore the Delta. She now lives on the shores of Point Richmond, where she watches the hawks nesting in giant eucalyptus trees and the ever-changing waters of the Bay. Laura studied literature and creative writing at Vassar College, then Latin American Studies at Stanford University, and has traveled widely in Latin America. A full-time journalist, she seeks balance in yoga and the natural world. Laura enjoys working on stories that celebrate human achievement, illuminate the arts, or explore the mysteries of our paths through life.

- By Laura Paull

- Photographs By: David Webster Smith

- 2 Comments

Leave a Reply

2 Comments

Unique and interesting story–and love the photographer’s perspective.

Really amazing story…the art is fantastic.