Little Trunk of Horrors

- By Tod Ruhstaller

- Photographs by Haggin Museum Archives

- August 26, 2020

- 6:00 pm

- One Comment

Although one of Stockton’s most intriguing court cases took place 114 years ago, it had all the elements that make today’s cable news networks salivate: sex, drugs and homicide.

Shortly after starting work at the Haggin Museum in the summer of 1984, I was familiarizing myself with our history collection one Saturday morning in the Storefronts Gallery when I came across a large trunk behind the counter of the drugstore display. Opening it, I found a hand-painted card thumbtacked to the blood-stained interior. It read: “The trunk in which EMMA LE DOUX put A.M. McVicar after killing him.”

Checking the museum records, I found that this grisly artifact was one of a number of artifacts donated to us in 1961 just prior to the demolition of the old San Joaquin County Jail on the northeast corner of Channel and San Joaquin Streets. Quite understandably, my curiosity was piqued, and I began to gather information about this artifact and the people and events associated with it.

Our story begins on Saturday evening, March 24, 1906 at Stockton’s Southern Pacific Depot. Earlier that afternoon an expressman had delivered a large trunk to the station for shipment on the 4:00 PM train to San Francisco. However, the trunk bore no baggage tags and was left at the station when the train departed.

Later that evening the station’s employees became suspicious when they traced a rather unpleasant odor that was permeating the baggage room to the unmarked trunk. Police were summoned and an officer arrived with both a search warrant and a chisel. He pried open the lock, lifted the lid and was met by the shoeless feet of a lifeless man.

Early the following morning the police began to run down their leads. The expressman told them that a woman had purchased the trunk from a local store on Saturday morning and had instructed him to deliver it to the California Hotel on the corner of Main and California Streets. She also told him to call for the trunk later that afternoon for delivery to the train station.

Police then questioned the California Hotel’s landlady who identified the body as that of Albert N. McVicar, who along with a woman she supposed was his wife, had checked into Room 97, on Friday, March 23.

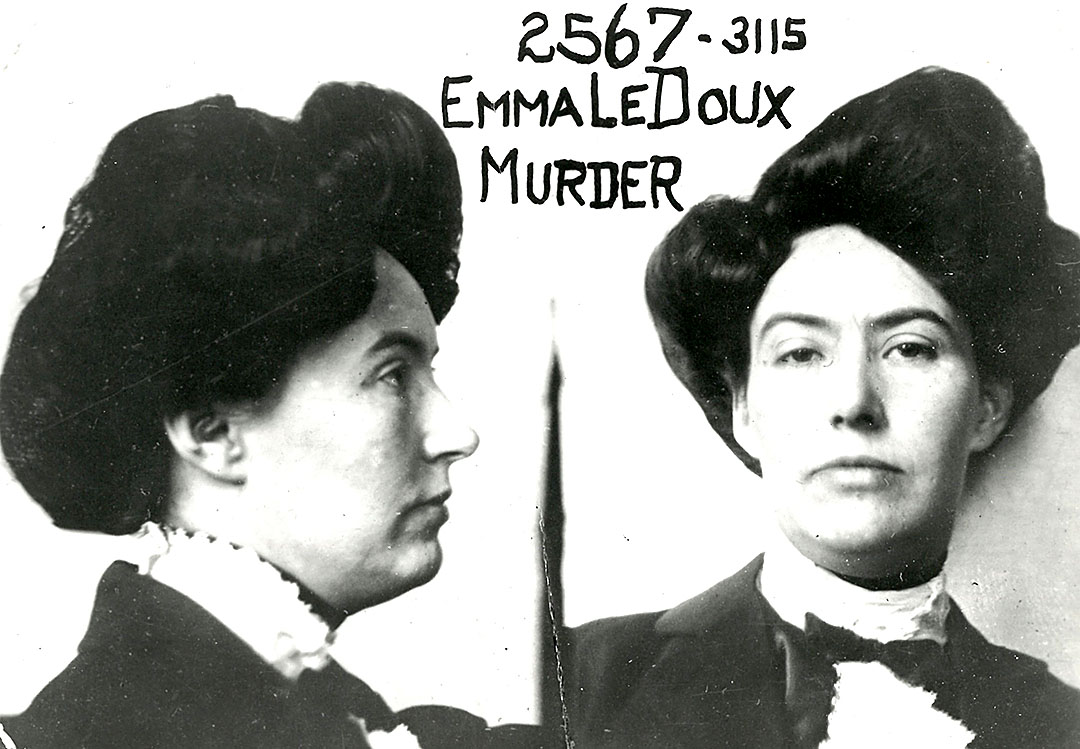

Based upon these interviews and photos of McVicker and the suspect found in a valise left behind in the room, police wired a detailed description of “Mrs. McVicar” to all towns between Stockton and San Francisco—the presumed destination of the mystery woman. On Monday morning a woman fitting the description was arrested in Antioch and brought back to Stockton that afternoon. In route she informed the authorities that her name was not McVicar, but LeDoux—Emma LeDoux.

By the time of her arrest, the news of the murder was the only topic of conversation in Stockton. Thousands of men, women and children had been allowed to parade past the remains of Mr. McVicar, whose autopsied body had been placed on public exhibition at the City’s morgue.

Stockton’s three daily newspapers—THE INDEPENDENT, THE MAIL and THE STOCKTON RECORD—took full advantage of the public’s curiosity. But the RECORD stole the show, devoting the entire front page of its Monday edition to the homicide with headlines, prose and photos that would make the editor of any supermarket check-out line tabloid proud.

The story had all the right elements. There was the local angle: it had happened in the heart of downtown Stockton. It was a murder with a twist: the attempt to enlist the Southern Pacific Railroad in the disposition of the victim’s body. And the evidence seemed to indicate that the alleged murderer was a woman with a questionable past.

She was born Emma Cole on September 10, 1875, and grew up around Jackson, California. First married in 1892 at the age of 16 to a 22-year-old man named Charles A. Barrett of Pine Grove, the couple divorced in January of 1898.

Emma then married a local miner by the name of William Stanley Williams about 1900. They moved to Bisbee, Arizona where he died in June of 1902 at the age of 30. The circumstances surrounding his death were somewhat suspicious, but it was finally determined that he died from heart failure. However, the fact that he was heavily insured was never in doubt.

On September 1, 1902—a little over two months after becoming a widow—Emma married Albert N. McVicar in Bisbee. She received a life insurance settlement of about $150,000 in today’s dollars and returned to California. Some accounts say with McVicar; others say without him.

Back in the Golden State she supported herself as a dressmaker and through the generosity of “gentlemen friends.” One such friend was Jean LeDoux, whom she married on August 26, 1905 in Woodland, California, albeit without the benefit of a divorce from husband number 3, the late Mr. McVicar.

Emma was indicted and entered a plea of not guilty on April 16. She might have remained the hot news item right up until the time of her trial, scheduled for May 22, had it not been an event which took place two days later. It’s worth noting that it took the great San Francisco earthquake and fire to bump Emma from page one.

Not only did the earthquake and ensuing fire steal the headlines, but they also caused the dispersal of witnesses and the destruction of material evidence. The trial was postponed until June 8, and by that time the local papers’ coverage of the Bay Area tragedy had waned and reporters could focus their attention once again on Emma.

Emma’s defense team was headed by Charles H. Crocker, a Jackson attorney and friend of Emma’s family, but it was noted Stockton attorney Charles Fairall who provided the criminal defense muscle.

District Attorney Charles Norton and Assistant District Attorney George McNoble represented the People. Both were highly regarded in the legal community and each realized the importance of this trial. It was a heinous crime and come November’s elections, a grateful public might see fit to bestow certain political rewards to those who helped make Emma pay her debt to society.

The presiding judge was the Hon. W. B. Nutter who reportedly spent months preparing for the case. He also was acutely aware of the trial’s popularity and increased the number of chairs in his courtroom and provided special tables for the press.

The trial began on June 5. Fairall immediately presented a challenge to the entire panel of jurors, arguing that Sheriff Walter Sibley, whose deputies had summoned the prospective jurors, had already formed an opinion as to the defendant’s guilt and was therefore incapable of assembling an impartial pool of jurors. However, the challenge was denied and the prosecution began its case.

The first group of witnesses served to connect Emma with the California Hotel, the trunk in which the body was found, and the Southern Pacific Depot.

In addition, a salesman for Bruener’s testified that he was familiar with both McVicar and LeDoux, as the couple had purchased some furniture the day before the murder and had asked that it be delivered to Jamestown in Tuolumne County. He also stated that Emma returned on the day of the murder and asked to have the furniture delivered to Jean LeDoux at Martel’s Station, just west of Jackson in Amador County.

Next Emma’s link to the victim’s death was presented. Because the interior of the truck was splattered with blood, early newspaper reports speculated that McVicar had died due to a blow or blows to the head. Instead, the coroner’s inquest ruled that:

“The deceased came to his death from the combined effects of morphine and chloral [knock-out drops], and, in a dazed condition, having been forced into a closed trunk where there was insufficient oxygen to sustain what life was present.”

The prosecution’s list of expert witnesses began with Dr. John F. Dillon, who testified that he had sold morphine to Emma when she was in San Francisco on March 13. Next, Dr. S. E. Latta, one of the doctor’s who performed the autopsy on McVicar, described the physiological effects of morphine poisoning and

told how the victim’s organs were shipped to San Francisco for chemical analysis. The forensic chemist who performed the analysis—Professor Roy Ravonne Rogers—testified that McVicar’s body contained 5 times the amount of morphine needed to kill a healthy male of McVicar’s size.

In an effort to establish a motive for the killing, and thereby prove murder in the first degree, the prosecution brought up the matter of bigamy. They contended that Emma saw McVicar as a threat to her relationship with Jean LeDoux, and that he might try to expose her bigamy.

It should be noted that Emma was hardly a homebody. While she was ostensibly LeDoux’s loving wife, she would leave him for weeks at a time to visit Stockton or San Francisco, usually in the company of other men. However, Mr. LeDoux, who was characterized by one reporter as “…broad-minded in the Gallic tradition…” valued his marriage, and as he pointed out, she always came home.

The prosecution ended its case with a bombshell from Professor Rogers. The coroner’s inquest had stated that death was due to poisoning and lack of oxygen in the trunk. But the prosecution maintained that death was due solely to the effects of the morphine and chloral, and if he had not been poisoned, McVicar would not have died in the trunk, as uncomfortable as it might have been.

Professor Rogers pointed out that because the trunk was not hermetically sealed, it could sustain human life indefinitely. In an effort to discount Rogers’ testimony, during cross-examination Fairall asked him if he would like to take his chances in the trunk under similar conditions. Rogers was quick to reply.

“I wouldn’t like it, but it would not injure me. I was shut up in it for 40 minutes this morning.”

Rogers explained he and the District Attorney had conducted an experiment to determine if one could breathe inside the trunk. District Attorney Norton sat on the trunk and Rogers curled up inside in the same position as McVicar. Stunned by Roger’s response, Fairall had no further questions.

The defense began their presentation on June 19 and opened with an attempt to disprove the prosecution’s alleged motive. A Mr. Garlinghouse was called to the stand to testify that Emma had once prostituted herself for McVicar’s benefit.

It was Fairall’s contention that any woman willing to do something this drastic for a man out of love, could never bring herself to then kill him. Nutter, however, refused to let Fairall develop this argument. This was a blow to the defense, which had lined up quite a number of witnesses to bear out their argument.

The defense had its own expert witnesses lined up, all with the sole purpose of refuting Professor Roger’s testimony and all contending that his analysis was both biased and inaccurate. Finally, the defense brought its case to a close by bringing Emma’s mother to the stand where she testified that her daughter was a habitual morphine user and had been for the last four or five years. She ventured the opinion that Emma may have enticed McVicar to take up the habit and that he had simply overdosed.

On June 20, the prosecution began its final rebuttal. Assistant District Attorney McNoble stressed the following points: McVicar’s death due to the effects of morphine poisoning and the fact that Emma had purchased some of the drug; she was linked to the trunk and its delivery to the train station; she had switched the destination of the furniture shipment; and that she was in a compromising, bigamous marriage to LeDoux. Nevertheless, it was all circumstantial.

In his closing remarks Defense Attorney Fairall pointed out that Emma was a morphine addict and could be expected to have the drug in her possession. He maintained that the chemical analysis of the victim’s organs had been faulty. And as for the motive presented by the prosecution—that Emma loved LeDoux and needed to dispose of a pesky extra husband—he replied:

“She didn’t love LeDoux. She could not love that pop-eyed woodchopper, who could neither read nor write, and was as deaf as a post. Women don’t love men like that. Women love men who are clear-eyed and hold their heads high like the lion.”

On Saturday, June 23, Judge Nutter read the jury its final instructions. There were three options open to them. They could find the defendant not guilty; they could find the defendant guilty of murder in the first degree and fix the penalty at life imprisonment; or they could find the defendant guilty of first-degree murder. The latter verdict, without a penalty recommendation, would be tantamount to a death sentence. Murder in the second degree and manslaughter were not options because McVicker’s death was due to poisoning.

At 2:30 in the afternoon the jury began their deliberations. They were out just over six hours and then returned to the courtroom.

Emma was found guilty of murder in the first degree with no penalty recommendation and was sentenced by Judge Nutter to hang on Friday, October 19, 1906 at San Quentin Prison. This was the first time in the history of California that a woman had been given the death penalty. At the same time, the sentence was automatically stayed by appeal to the State Supreme Court.

Emma’s appeal took quite some time. It was originally to be heard in the summer of 1907, but it wasn’t until May of 1909 that a decision was handed down. That’s a lot of time to wait in the San Joaquin County jail.

Like many convicts, Emma turned to religion and became a member of St. Mary’s Church. Her addiction to morphine was real and her withdrawal was rather difficult. And with some time on her hands Emma entered a newspaper contest and won $92.00 from a local music store. Unfortunately, it could only be applied to the purchase of a grand piano.

Nevertheless, as it turned out the State Supreme Court ordered a new trial. The decision was based, for the most part, on the Court’s belief that Sheriff Sibley had indeed biased the selection of the jurors. Set for January 25, 1910, the new trial never took place. The two sides obviously had struck a deal, each for their own reasons.

The D.A. realized that another trial would cost the County an additional $10-15,000. The defense was aware of the fact that the jury had reached its guilty verdict very quickly; the only reason they were out for six hours was because they originally had split on the penalty to be imposed.

On January 26, 1910 Emma appeared in court once again, but this time, through her attorney Charles Fairall, she pled guilty. Citing her poor health as a reason for not contesting the charge, Fairall went on to say that Emma did not kill McVicar. Instead she had found him dead when she returned from shopping on that Saturday morning. Fearing no one would believe her, she panicked, put the body in the trunk and fled. Accepting her plea, Judge Nutter sentenced her to life in prison. On February 2, 1910 Emma was transferred to the women’s block of San Quentin Prison.

Charles Crocker returned to Jackson and later moved his practice to Sacramento. Charles Fairall had become quite well known for his defense of Emma and went on to become a prominent San Francisco attorney. And as expected, the voters of San Joaquin County rewarded the prosecution team. District Attorney Norton was made a superior court judge and Assistant District Attorney McNoble was given his boss’ old job. Judge Nutter remained on the bench for a number of years before returning to his private law practice.

But what of Emma? Well, seven years after her arrival at San Quentin she began to petition the State Parole Board. After three denials, she was finally granted parole on July 20, 1920.

Unfortunately, things did not go that smoothly for Emma on the outside. Paroled to the custody of a sister living in the Los Angeles area, she was back at San Quentin in less than a year. Her sister and brother-in-law had testified that she had been associating with men in a less than respectable manner, coming home inebriated on numerous occasions, and carrying on an inappropriate relationship with their 19-year old son.

It took three more years, but Emma was paroled once again on March 30, 1925. Sometime around 1926 she married a Bay Area man by the name of Fred A. Crackbon, someone who apparently never spent much time reading newspapers. He died of a stroke in August of 1929.

There followed a series of run-ins with the law, including a bad check charge and a vagrancy charge, both of which were dropped. But when it was discovered that she was running a bogus matrimonial service, with herself as the sole object of lonely men’s attention, her parole was revoked once again and she headed back to San Quentin in April of 1931.

She was transferred to the new California State Prison for Women at Tehachapi in November of 1933. For two more years she submitted applications to the parole board, but after both were denied, she gave up. On July 7, 1941 Emma died of ovarian cancer at the age of 69, still a prisoner of the State of California.

Some might say that she missed true notoriety by not becoming the first woman legally hanged by the State of California. No doubt Emma would have considered that a rather dubious distinction. Instead she may very well have taken no small measure of satisfaction in knowing that she had outlived all of the principal players in her 1906 trial.

###

A Stockton native, Tod Ruhstaller has been with the Haggin Museum for nearly 36 years, first as its Curator of History and currently as its CEO. Previously he was a field archaeologist for Far Western Anthropological Research Group. He considers coming to work at the Haggin to be the second best decision he’s ever made; marrying his wife Sandi will always be Number 1.

- By Tod Ruhstaller

- Photographs By: Haggin Museum Archives

- August 26, 2020

- 6:00 pm

- One Comment

Leave a Reply

One Comment

Thank you, Tod Ruhstaller. Great story of Emma LaDoux and the grizzly find at the Haggin.