Paradise Lost

An Indigenous History Timeline for the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

- By David Stuart

- June 25, 2021

- 11:17 pm

- No Comments

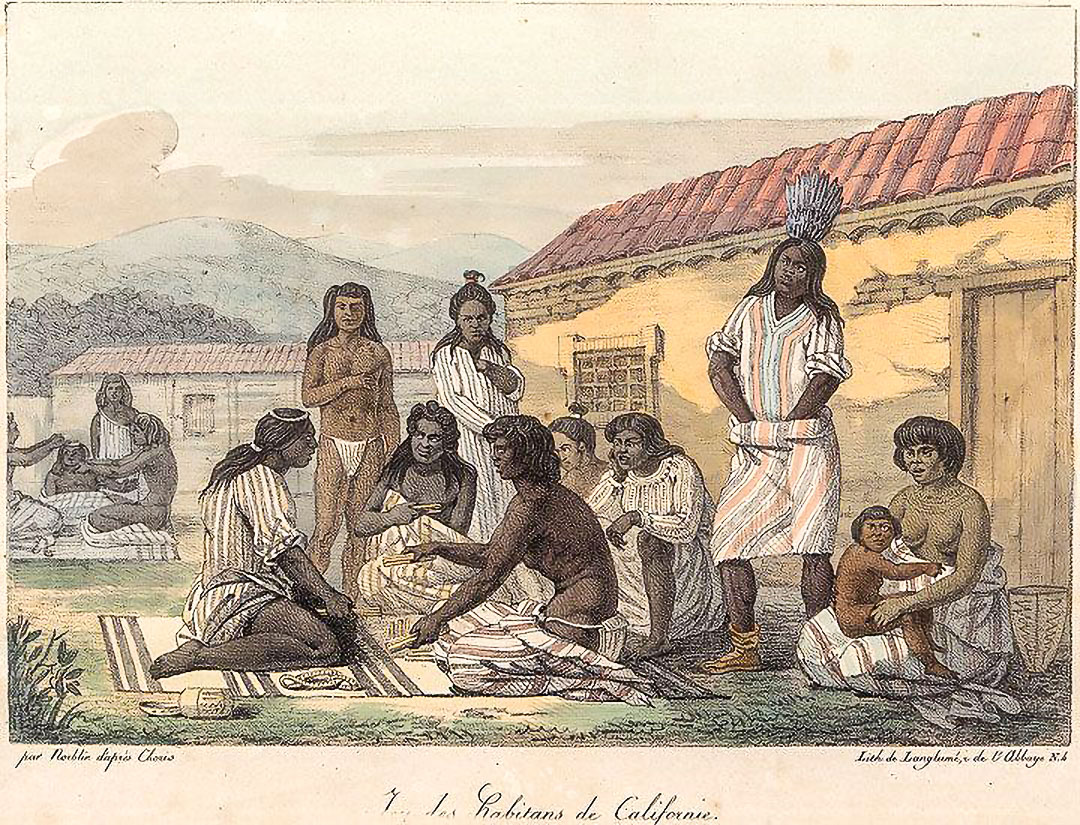

For thousands of years, Indigenous people lived in the heartland of California, where the Sacramento Valley from the north and the San Joaquin Valley from the south merge, near the largest estuary on the Pacific Coast of the American continents. Many sovereign Native nations had populous year-round towns and homeland territories on all margins of California’s delta—communities that changed little for two thousand years prior to the Spanish invasion of the San Francisco Bay Area. Then, about 250 years ago, all hell broke loose….

This timeline was assembled to support the preparation of a master plan for the new Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta National Heritage Area. Three contemporary Native nations have representatives contributing to that planning effort, providing traditional knowledge to complement this synthesis of historical and anthropological documentation.

As early as 30,000 years (1,500 generations) ago: Multiple migrations from northeast Asia initially peopled the Americas via several routes, including the “kelp highway” route along the Pacific coast. There is no evidence (yet) of these earliest people in interior California.

15,000-11,000 years (750-550 generations) ago: Indigenous people occupied the California heartland at the end of the last Ice Age, when so much of Earth’s water was locked up in glaciers that the present San Francisco, San Pablo, and Suisun Bays were mere river canyons and the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta (“the Delta”) had not yet formed. Low density, mobile groups from this period are evidenced by distinctive spear points found on all peripheries of the current Delta.

7,000-5,000 years ago: Melting Pleistocene ice raised sea levels several hundred feet and the bays and the Delta formed.

About 5,500 years (275 generations) ago: Native immigrants from the northwestern Great Basin and the Columbia Plateau moved into the east side of the Delta, perhaps leaving the shores of shallow lakes that dried up due to a prolonged climate fluctuation. These direct ancestors of the Miwok-speaking peoples developed a “Delta-river” way of life that emphasized fishing and waterfowl hunting. About 4,000 years (200 generations) ago, Miwok-speakers expanded into the Bay Area and Coastal Range and more recently into the Sierra foothills.

By about 2,000 years (100 generations) ago: Many Indigenous nations in the Delta had settled into the same year-round towns with up to 400 or 500 people and the homeland territories (about ten miles across) that were later recorded by the Spanish. These sovereign nations had very dense and perhaps growing populations (the densest in Indigenous North America, except Central Mexico), sustainable management of homeland landscapes and resources, extensive trade networks, and rich cultures—what some early anthropologists considered “classic” California Indian cultures because they were least influenced by the Native cultures of the Pacific Northwest or the American Southwest. (See Deep History of the Delta article.)

1,500-1,000 years (75-50 generations) ago: Patwin-speaking nations moved south in the Sacramento Valley into the north edge of the Delta (the Sacramento River Delta), perhaps encouraged by expanding Wintun-speakers farther north. Nisenan-speaking nations apparently migrated into the American and Feather River corridors—their language indicates a more-recent immigration from the Great Basin. Lastly, the Yokuts-speaking nations expanded into the southern Delta (the San Joaquin River Delta) moving north in the San Joaquin Valley.

1500s (24 generations ago): Spain colonized Mexico. Brief European ship contacts with coastal California Indigenous nations (e.g., Francis Drake in 1579) likely introduced diseases to which Native peoples had little resistance. Trade networks probably spread those deadly new diseases to Indigenous nations in the Delta.

1770s-90s (12 generations ago): To protect Spanish colonial enterprises in Mexico from other European colonial nations expanding in North America, especially Russia and Great Britain, Spain invaded and colonized coastal California. The Spanish plan was to usurp Indigenous lands and resources; control and gather the Natives living in a region into one central mission site (a process called reducción or reduction); use forced Native labor to create pueblos (towns); and convert the Indians to Catholicism, Spanish language, and Spanish culture—a process now recognized as cultural genocide. The desired result was to totally absorb Native people into Spanish colonial society—filling the largest and lowest rung in the caste hierarchy—and to create self-supporting frontier communities as a buffer against other colonial powers that might threaten Spanish empire interests.

Spain occupied the homelands of San Francisco Bay Area Indigenous nations, established mission communities—Mission San Francisco de Asís (also known as Mission Dolores) established in 1776-7 on the desolate north end of the peninsula and, forty miles south in the fertile Santa Clara (now Silicon) Valley, Mission Santa Clara de Asís in 1777—and a presidio (garrison of soldiers), and explored the East Bay and south shore of Carquinez Strait.

Native peoples were quickly devastated by introduced diseases; abuse by Spanish soldiers, priests, and citizens; and the destruction of Native food/healing resources, intertribal alliances, marriage/kin relationships, and traditional trade networks. In the years after establishment, the Bay Area missions had no willing Native converts/laborers and the Indigenous men fought the Spanish soldiers. Many Native people fled inland to find refuge in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

In the mid-1790s, many Bay Area Indians committed to baptism at the missions, apparently because “a critical mass of [Native] people developed a sense that they had no alternative to joining the Spanish system in the face of ongoing high death rates from unknown diseases, selective arrests of resistance leaders, [loss of homeland resources,] and threats of damnation from some of the Franciscan priests” (Milliken, Native Americans at Mission San Jose, p.33).

“[A]mbivalent native villagers along the mission-tribal frontier struggled with a choice—find a place in the new mission system or resist its attractions. The decision to reject mission life could be made a thousand times, but the decision to join a mission community could be made only once” (Milliken, A Time of Little Choice, p. 11). Once baptized, the “mission Indians” were prisoners under strict Spanish control and were hunted down by Spanish soldiers if they attempted to return without permission to their home villages or sought to escape inland to the California heartland.

Periodic epidemics of common European diseases such as measles and influenza killed many Native converts confined at the missions (and spread to the remaining villages); tuberculosis, syphilis, and food- and water-borne diseases became endemic at the missions; unsanitary conditions, crowded common sleeping quarters in which unmarried Native converts were locked each night, and poor nutrition fostered illness and death. Before the Spanish arrived, Indigenous nations had steady, balanced birth and death rates of about 65 per 1000; at Mission San José (see below) the death rate skyrocketed to approach 200 per 1000. Moreover, women converts died at a much higher rate than men, depressing birth rates, and less than 1/3 of Indigenous babies born at the missions survived to their fifth birthday. It was difficult for the Spanish to recruit enough new converts to maintain the desired labor force.

1797-1801: Twenty years after the founding of the original Bay Area missions, Mission San José was established farther inland (present-day Fremont), in part to recruit Native workers/converts from the Delta and northern San Joaquin Valley to “replace” coastal Indians. “It would certainly have been built further inland, in the Livermore or Diablo valleys, were it not for Spanish concerns about the hostile Saclans only 25 miles further north” (Milliken Native Americans at Mission San Jose, p. 37).

The Bay Miwok-speaking Saclan nation had gone to Mission San Francisco de Asís in 1795 yet fled soon after due to an epidemic at the crowded mission. The fugitive Saclan were joined by several hundred other Indian escapees and the Saclan led a fierce resistance from what is now west-central Contra Costa county until 1801.

1806: A measles epidemic hit Missions San José and San Juan Bautista in late February and in April ravaged Missions Santa Clara de Asís and San Francisco de Asís. It appears to have spread from the Southern California missions via the San Joaquin Valley and the Delta, thus many Delta Natives were likely infected and many probably died. At Mission San José, in a month and a half the disease killed 20% of the captive Native women, 13% of the men, and 16% of the children.

1807: Townspeople from the first Bay Area Spanish pueblo (civilian town), San José de Guadalupe near Mission Santa Clara de Asís (now the City of San Jose), needed Indian laborers because almost all local Natives had already moved to nearby missions. Spanish authorities allowed the civilians to recruit workers from the Yokuts-speaking Cholvomne nation from the south Delta (near modern Tracy).

1806-08: Expeditions of Spanish priests and soldiers entered the Delta, seeking new Native converts to move to Mission San José. Indigenous nations fled and/or defended their homelands rather than acquiesce to the pressure.

1809-10: Many members of the large Coastanoan (or Ohlone)-speaking Carquin nation, from the Carquinez Strait area (modern Crockett, Port Costa, and Martinez on the south shore; Vallejo and Benicia on the north shore), went to Mission San Francisco de Asís.

1811-12: People from the Ompin (probably Bay Miwok-speaking) nation from the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers across from modern Pittsburg and from the Julpun (probably Bay Miwok) nation of present northeastern Contra Costa county moved to Mission San José. A minority of the members of these nations found refuge in the Sacramento River Delta with nations such as the Ochejamne (near present Courtland).

1809-13: Spanish military campaigns sent to capture and return fugitive “mission Indians” caused many Natives from Yokuts-speaking nations in the San Joaquin River Delta to move to Mission San José—e.g., Cholvomne (from near Tracy), Tamukamne/Tamcan (Byron), Coybos (Lathrop), and Josmite (Vernalis).

For example, the Cholvomne were having a ceremony when Spanish forces of 23 soldiers and 50 armed “mission Indian” auxiliaries attacked at dawn without warning. Casualties were not reported, but the expedition returned to Mission San José with a reported 15 escapees, 18 “heathen men,” and 51 “heathen women.”

1810-16: Following a Spanish attack on their nation in 1810, many of the Patwin-speaking Suisun left their homelands on the north shore of Suisun Bay (present Fairfield) to live at Mission San Francisco de Asís, the first Patwin-speakers to move to a Spanish mission. Their fellow Patwin-speakers, the Napa, went not to Mission San Francisco de Asís, but initially to Mission San José at about the same time.

1812-13: The Anizumne (Miwok-speakers from near modern Rio Vista) moved to Mission San José in 1812, but within a year many rejected captive mission life, escaped, and found refuge with the Unizumne (Miwok near Walnut Grove). Twelve Spanish soldiers and 100 “mission Indian” auxiliary forces were sent in boats to retrieve the escapees. They engaged the Native defenders from four local nations in one of the first battles in the Sacramento River Delta. The number of Native men killed or wounded was not reported, but the soldiers and auxiliaries returned to Mission San José with no fugitive Anizumne in custody.

1813-30: Miwok-speaking nations from the lower Mokelumne River (e.g., Muquelemne from near Lodi), the lower Cosumnes River (e.g., Cosomne from south of Elk Grove), and the Sacramento River Delta (e.g., Ochejamne and Unizumne from near modern Courtland and Walnut Grove) strongly resisted Spanish intrusions and protected Bay Area Native refugees (see entries above and below on noteworthy battles). These powerful nations—and some Yokuts-speaking nations farther south along the Stanislaus River and the southeast Delta—were sometimes called the “horse thief Indians” because of their mounted raids upon the mission herds.

In 1819, forty additional soldiers were assigned to the San Francisco presidio and were trained to thwart the raids. Many of the Spanish punitive expeditions were not documented, but one attack in late 1819, for example, killed 27 Muquelemne, wounded 20 others, and took 16 captives.

1814-20: Many people from Yokuts-speaking nations in the San Joaquin River Delta and the southeast periphery of the Delta moved to Mission San José—e.g., Jalalon (near Old and Middle Rivers), Nototomne (French Camp), Yatchicumne (Stockton), and Lacquisemne (Ripon).

A village near present-day Stockton was attacked in 1818 by 25 soldiers backed up by “mission Indian” auxiliaries. Twenty-seven villagers were murdered. “Those who did not fall into our hands escaped into the brush,” wrote one Spanish soldier. “There must have been many wounded among them. After firing a rifle volley at them we charged with our lances and slaughtered them.” About 50 Natives were taken to the presidio at San Francisco, where they “were put at hard labor—at that time the main quarters were being built” (Cook, “Colonial Expeditions to the Interior,” p. 196).

1821-25: Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, but it took a year for the news to reach the California coastal frontier and a few years for the new nation to really assume colonial control of coastal California.

1826: The Cosomne nation (Miwok-speakers south of modern Elk Grove) routed a large invading force of soldiers from the San Francisco presidio. Later that year, the Mexicans returned with more soldiers and cannon, killed 41 Cosomne men, women, and children and took 40 women and children as slaves.

1824-28: After a “war of attrition,” several Native nations from the south-central Delta went to Mission San José—e.g., Musupumne (Miwok-speakers from Staten Island) in 1824; Tauquimne (Yokuts from the mouth of Bear Creek north of Stockton) in 1825; Quenemsia (Miwok from near Ryde) in 1826; and Unizumne (Miwok from near Walnut Grove) in 1827-28.

The Unizumne and Quenemsia had been among the leaders of Sacramento River Delta resistance against the Spanish/Mexicans for more than a decade, but apparently were discouraged by the recent defeat of their powerful ally, the Cosomne (see above).

1826-27 (9.7 generations ago): The first American trappers, a small group led by Jedediah Smith, entered California from the east, traveled up the San Joaquin Valley, and began trapping in the eastern Delta (the American River is named for them). They skirmished with Nisenan- and Miwok-speaking nations, but peacefully bivouacked on the Stanislaus River among Yokuts-speakers, then exited north through the Sacramento Valley and north coast into Oregon country. In the Pacific Northwest, the British Hudson’s Bay Company learned about the rich trapping grounds in the Delta from the Americans.

The lack of any military response by the Mexican government to the unauthorized intrusion of the American trappers may have emboldened Indigenous nations to resist Mexican efforts to control the California heartland.

1828-29: The so-called “Estanislao’s Rebellion” began when hundreds of Indians escaped from Missions San José, Santa Clara de Asís, and—to a lesser extent—San Juan Bautista and returned to their homelands on the Stanislaus River and the southeast Delta. They formed a loose multi-national band of freedom fighters dedicated to keeping the Mexicans on the coast and out of the Delta and San Joaquin Valley. The Native patriots were led by a Lacquisemne (Yokuts-speakers from near present Ripon) man named Cucunuchi—renamed Estanislao at Mission San José in 1821—and a Josemite (Yokuts near Vernalis) man named Huhuyut—renamed Cipriano at Mission Santa Clara de Asís.

In November 1828, the insurgents defeated Mexican soldiers sent to chastise them and force their return. In early May 1829 (after the wet season, during which travel was impossible), the Native patriots were again victorious in a larger battle, primarily because they had built defensive earthworks and gathered a large fighting force. In late May, the largest army ever assembled in Hispanic California—104 soldiers from the presidios at Monterey and San Francisco, 50 “mission Indian” auxiliaries, plus citizen volunteers—was deployed by the Father-President of the missions and the commander of the San Francisco presidio. The army was led by a young Californio (Californian of Spanish descent) from a prominent family, second lieutenant Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo. The imposing Mexican army used cannon and set the riparian woods on fire, but the third and final battle was a draw—the Native freedom fighters neither conceded their territory nor surrendered.

Three captured Native women were murdered by the Mexican troops and many children were taken to the presidios as slaves. Recruitment of new converts at the Bay Area missions drastically declined and did not increase for five or more years, apparently in reaction to the battles, contributing to Mexico’s decision to discontinue the mission system (see below). The Stanislaus River and Stanislaus County were later named for Cucunuchi/Estanislao. See Homeland Defense article.

1830: A boat expedition from Mission San José went up the Sacramento River seeking mission escapees. When the Ochejamne (Miwok-speakers from near Courtland) refused to give up fugitives they had taken in, the Mexican soldiers recruited odd allies to bolster their forces: members of nearby Miwok-speaking nations including the Cosomne, Ylamne, and Siusumne. Because those nations had traditionally been trading partners or associates of the Ochejamne, this alliance indicated a rift between the Ochejamne-Unizumne (from near Walnut Grove) nations and their neighbors to the north; it also illustrates the volatility of the historic period, characterized by constantly shifting conditions upon which Indigenous nations had to base decisions.

The allied Mexican-Native nations attacked, but the Ochejamne forced them to retreat with several wounded men. As luck would have it, the Mexicans encountered and enlisted another group of allies: eleven American trappers led by Ewing Young. The Mexicans, Americans, and allied Natives attacked and forced the Ochejamne to burn their own village and retreat into the Delta. Within months, more than 300 members of the Ochejamne nation moved to Mission San José, the largest single group from the Delta or Central Valley to be baptized at any Bay Area mission.

1829-45: The Hudson’s Bay Company sent trapping/trading brigades from Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River into California’s Sacramento Valley and the Delta. The brigades rendezvoused at what is now called French Camp. As was the Company’s practice, the large brigades quickly and severely reduced desirable fur-bearing mammals and other game and natural resources.

1832-33 (9.4 generations ago): Hudson’s Bay trappers unwittingly brought malaria from Oregon country into the mosquito-filled wetlands of the Central Valley. Within months, 75-80% of Delta and Valley Indians died from the epidemic, one of the most catastrophic plagues in California history.

Trappers passing through the Central Valley were struck by the rapid impact of the disease:

…late in the summer of 1833 we found the valleys depopulated. From the head of the Sacramento [Valley] to the great bend…of the San Joaquin [River near modern Fresno], we did not see more than six or eight [living] Indians; while large numbers of their skulls and dead bodies were to be seen under almost every shade-tree near water, where uninhabited and deserted villages had been converted to graveyards; and on the San Joaquin River, in the immediate neighborhood of the larger…villages, which, the preceding year, were the abodes of a large number of these Indians, we found not only many graves, but the vestiges of a funeral pyre” (Cook, “The Epidemic of 1830-33,” p. 12.)

1833: A group of Mexican citizens from the pueblo (civilian town) near Mission Santa Clara de Asís (modern San Jose), led by Sebastian Peralta, sought to return Indian runaways—the pueblo’s low-wage laborers—and to punish the Natives from the interior for raiding the herds of the missions and pueblo. The vigilantes arranged a meeting with the powerful Muquelemne nation that had provided sanctuary to the runaways and was the predominant raiding nation. During the meeting, the Mexicans suddenly attacked—even though most of the Muquelemne were not armed—and at least 22 Natives were killed. The Calaveras River may have been named for the Indigenous bodies left at the site of this massacre (calaveras is “skull” in Spanish), probably unburied because the malaria epidemic struck at the same time.

1833-34: Some of the survivors of the malaria plague from Miwok-speaking nations of the Sacramento River Delta went to Mission San José—e.g., Gualacomne (south of Freeport), Ylamne (Clarksburg)—whereas other nations remained strong enough to stubbornly continue resisting missionization—e.g., Chupumne (near Hood), Siusumne (Courtland). Other nations abandoned their villages and homelands after the malaria epidemic—e.g., Hulpumne (near Freeport), Unizumne (Walnut Grove).

1837-38: A smallpox epidemic that originated at Fort Ross, the Russian settlement on the Sonoma coast, spread through the surviving Indigenous communities in the Delta and may have encouraged the dispersal of “mission Indians” from Bay Area missions as Mexico discontinued (secularized) the missions. Some “mission Indians” whose homelands were in the Delta formed new multi-national Native communities—e.g., one on the Sacramento River was comprised of Gualacomne, Ochejamne, and Chupumne refugees, another west of Pleasanton was even more diverse. Some Native people returned to the vicinity of their original homelands in the Delta, but none reestablished control of tribal territories. Indigenous homelands in and adjacent to the Delta became “public domain”—some given away as land grants by the Mexican government, some later sold by the State of California.

1837 (9.2 generations ago): American John Marsh acquired a rancho (ranch) on the east base of Mt. Diablo (near modern Brentwood), homeland of the Bay Miwok-speaking Volvon nation. When Mission San José was discontinued in 1837-39 the captive Indians were turned out and many—including many originally from the Delta—moved to Marsh’s rancho, as well as to other Coastal Range ranchos.

Marsh was a booster encouraging American settlers to come to California. He wrote to Missourians:

In many instances when a family of white people have taken a farm in the vicinity…in a short time they would have a whole tribe as willing serfs. They submit to flagellation with more humility than the negroes. Nothing more is necessary for their complete subjugation, but kindness in the beginning, and a little well timed severity when manifestly deserved…. Throughout all California the Indians are the principal laborers, without them the business of the country could hardly be carried on (Milliken, Native Americans at Mission San Jose, p. 76).

1834-1840: In recognition of Mariano G. Vallejo’s service in the final battle with the Indigenous insurgents in “Estanislao’s Rebellion” (see above)—and his family’s status—he was granted 66,600-acre Rancho de Petaluma (in ten years the rancho would grow to 175,000 acres). It was land that had been controlled by Mission San Francisco Solano, and comprised the homelands of Coast Miwok-, Southern Pomo-, Wappo-, and Patwin-speaking Native nations. Vallejo became a paternalistic protector of many of the surviving Indians, mostly Patwin-speakers, including influential Chief Solano. Hundreds of Indigenous people were Vallejo’s serfs—and his soldiers.

The colonial influence exerted over Delta Natives by the Bay Area missions waned and was assumed by Vallejo, and to a much lesser extent, other Coastal Range rancho owners (e.g., Ygnacio Martinez, Commander of the San Francisco presidio, at Rancho El Pinole near present-day Martinez and Antonio Pico at Rancho Pescadero near modern Tracy). Vallejo’s influence extended to the lower Sacramento River and the north edge of the Delta.

In 1837, Vallejo entered a “mutual defense pact” with the Ochejamne and Siusumne (Miwok-speakers from near Courtland). A year later, those Delta nations attacked the Muqulemne (Miwok from the Lodi area) and retrieved horses stolen from Vallejo. Muqulemne raiders were soon defeated at the entrance to the Napa Valley before they had reached Sonoma pueblo.

1839-47: Swiss expatriate John Sutter and a small group including eight or ten Native Hawaiians (“Kanakas”) traveled by boats through the Delta to found New Helvetia, a “feudal barony,” an agricultural/trading enterprise centered near the confluence of the American and Sacramento Rivers (now Sacramento), near the Nisenan-speaking Pusune and Sicomne villages. The “barony” soon expanded north up the Sacramento Valley to include the significant Nisenan village Hok, on the Feather River near its confluence with the Bear River (south of modern Yuba City).

The Nisenan-speakers had been less impacted than other Delta Indigenous nations by the Bay Area missions because the Delta wetlands and the freedom-fighting nations on the east edge of the Delta were a barrier to Spanish/Mexican intrusions. Many Nisenan-speakers and Miwok- and Yokuts-speaking people from the Delta eventually became minimally-paid workers (serfs)—some researchers consider them slaves—for Sutter (trappers, soldiers, herdsmen, farm laborers, craftsmen, etc.).

The Cosome (Miwok-speakers originally from the Cosumnes River corridor south of modern Elk Grove) twice attacked New Helvetia shortly after its founding, trying to displace Sutter, but both attempts failed—Sutter had brought three cannon, muskets, rifles, powder, and shot with which to defend his empire. Thus, colonial power shifted from Vallejo and Sacramento River Delta Indigenous nations aligned with Sutter.

In 1840, the Ochejamne participated a raid in the Napa Valley and they abandoned their homeland in the Sacramento River Delta to live at Sutter’s New Helvetia. That same year, Sutter recruited the remaining members of the Gualacomne (a large nation south of present Freeport) to join with the Ochejamne and attacked and defeated the Cosomne. After that defeat, many members of the large Cosomne nation moved to Mission San José and those that remained in their homeland moved to live near Sutter’s Fort by 1844.

The Muquelemne (Miwok-speakers originally from the Mokelumne River corridor near modern Lodi) took control of former Cosomne homelands along the Cosumnes River (south of present Elk Grove) and in 1843 established a village on the Cosumnes River at which they farmed until at least 1855. The Muquelemne provided about 100 warriors to serve under Sutter in support of Mexican governor Micheltorena in 1845. Soon after, Mexican assassination plots against Sutter were revealed to have been aided by some Muquelemne leaders; therefore in 1846, Sutter attacked and killed many Muquelemne near the Calaveras River (east of modern Stockton).

1844: The Mexican governor authorized a land grant to German immigrant Charles Weber’s partner—soon acquired by Weber—in the vicinity of modern Stockton. The area of Weber’s grant had been largely depopulated of Indigenous peoples, but Weber struck a friendship and agreement with Native leader José Jesús that allowed the peaceful American occupation of Stockton and San Joaquin County.

After the Mexican government discontinued Mission San José, ten families originally from the Yatchicumne nation (Yokuts-speakers from present Stockton) had moved to José Amador’s Rancho San Ramon, but into the 1850s they made annual visits to their homeland and exchanged gifts with Weber.

1846-48: The United States declared war on Mexico and coincidently (or not) John Frèmont and his heavily armed U.S. Expedition arrived at Sutter’s New Helvetia. Sutter and his Native allies supported the Americans against Mexico. Several Indigenous men joined the California Battalion at Sutter’s Fort, apparently from Delta Indigenous nations including the Muquelemne, Cosomne, Ochejamne, Gualacomne, and Ylamne.

###

For a summary of the lifeways of a representative Indigenous nation from the Sacramento River Delta, see Deep History of the Delta article. For additional information, see these sources:

Bancroft, Herbert H. History of California. San Francisco, CA: History Company, 1886-90.

Bennyhoff, James A. Ethnogeography of the Plains Miwok, Center for Archaeological Research at Davis, number 5. Davis, CA: University of California at Davis, 1977.

Cook, Sherburne F. “The Epidemic of 1830-1833 in California and Oregon.” University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology, 43, number 3 (1955): 303-25.

Cook, Sherburne F. “Colonial Expeditions to the Interior of California: Central Valley, 1800-1820.” University of California Anthropological Records, 16, number 6 (1960): 239-92.

Cook, Sherburne F. “Expeditions to the Interior of California, Central Valley, 1820-1840.” University of California Anthropological Records, 20, number 5 (1962): 151-213.

Heizer, Robert F., ed. Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 8 (California). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1978.

Jones, Terry L., and Kathryn A. Klar, eds. California Prehistory: Colonization, Culture, and Complexity. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield/Alta Mira. 2007.

Milliken, Randall. Native Americans at Mission San Jose. Banning, CA: Malki-Ballena, 2008.

Milliken, Randall. A Time of Little Choice: The Disintegration of Tribal Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1769-1810. Banning, CA: Malki-Ballena, 2009.

Phillips, George H., Indians and Intruders in Central California, 1769-1849. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993.

Stuart, David R., “The Native Peoples of San Joaquin County: Indian Pioneers, Immigrants, Innovators, Freedom Fighters, and Survivors,” The San Joaquin Historian, Lodi, CA: San Joaquin County Historical Society, Part One Summer 2016, Part Two Winter 2016.

David Stuart recently retired as the executive director of the San Joaquin County Historical Society. Previously, he directed the Sacramento History Museum, the Sacramento Science Center, and museums in Ventura. His family settled in the Delta in 1860.

- By David Stuart

- June 25, 2021

- 11:17 pm

- No Comments

Leave a Reply